Steel is one of the most essential engineering materials in modern manufacturing. Its properties are determined by chemical composition, purity, metallurgical reactions, solidification behavior, and subsequent thermo-mechanical processing. For designers and manufacturing engineers, understanding how steel is made helps support better decisions in material selection, casting feasibility, and cost evaluation.

What Is Steel?

Steel is an iron-based alloy containing 0.02–2.1% carbon, with additional alloying elements such as chromium, nickel, molybdenum, manganese, vanadium, or niobium depending on performance requirements. Its final properties are influenced not only by composition but also by oxygen content, inclusion morphology, grain structure, and heat-treatment history. Steelmaking is therefore a system focused on composition design, purity control, and microstructure engineering.

A Brief History of Steelmaking

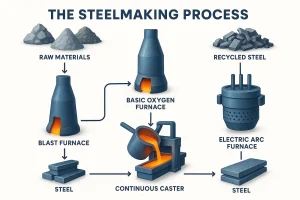

Since the introduction of the Bessemer converter in the 19th century, steelmaking has replaced wrought iron and evolved into a modern metallurgical system with two major raw-material routes:

- Ore-based route: Iron ore is reduced to hot metal in a blast furnace and then refined in a basic oxygen furnace (BOF) for rapid decarburization.

- Scrap-based route: Scrap steel or direct reduced iron (DRI) is melted and compositionally adjusted in an electric arc furnace (EAF), offering greater flexibility and the potential for lower carbon emissions.

With the advancement of low-carbon metallurgy, DRI has become an increasingly important iron unit for the EAF route, enhancing both steel purity and process stability. Regardless of the starting material, the actual steelmaking process begins inside the BOF or EAF, where critical metallurgical reactions—decarburization, impurity removal, and compositional control—determine the fundamental properties of the final steel.

How Steel Is Made?

Modern steelmaking consists of three main stages: primary steelmaking, secondary steelmaking, and casting/solidification. Together, these determine the alloy framework, purity level, and internal structure of the final steel product.

Primary Steelmaking

Primary steelmaking transforms hot metal or scrap into molten steel with the required base chemistry while removing carbon, silicon, phosphorus, sulfur, and other impurities. This stage establishes the fundamental alloy framework.

In the ore-based route, the basic oxygen furnace (BOF) uses high-purity oxygen to achieve rapid decarburization, making it the dominant method for producing carbon steel and low-alloy grades.

In the scrap-based route, the electric arc furnace (EAF) melts scrap through high-temperature electric arcs and offers flexible alloy adjustment, making it suitable for stainless steels and high-alloy compositions.

Direct reduced iron (DRI) is produced by reducing iron ore with natural gas or hydrogen in the solid state. Because of its low impurity content and stable chemistry, it is often used as a high-quality iron source in EAF operations to enhance steel purity and process consistency. With the rise of low-carbon metallurgy, the DRI + EAF route is expanding rapidly.

Secondary Steelmaking

After primary steelmaking, the molten steel has the correct basic composition but requires further purification to achieve low inclusion content, low gas levels, and stable mechanical properties. Secondary steelmaking is the critical stage for purity control and performance consistency.

Typical ladle-metallurgy treatments include deoxidation, desulfurization, degassing, slag refining, and inclusion engineering. These processes significantly improve toughness, weldability, and fatigue resistance.

This stage also includes precise alloy trimming, where elements such as Cr, Ni, Mo, V, and Nb are added to meet specific mechanical and application requirements.

Casting & Solidification

Refined molten steel is typically shaped through continuous casting, forming slabs, blooms, or billets. The solidification process determines the steel’s internal quality, including density, segregation, shrinkage behavior, and grain uniformity.

After solidification, the steel undergoes hot rolling or cold rolling to refine the grain structure, improve dimensional accuracy, and enhance surface quality, resulting in finished steel products ready for manufacturing and machining applications.

Major Types of Steel

Steel grades are generally classified into three broad categories:

- Carbon Steel: Strength and hardness are controlled primarily by carbon content; widely used in structural and mechanical applications.

- Alloy Steel: Contains Cr, Ni, Mo, Mn, V, or other alloying elements to improve hardenability, wear resistance, and high-temperature performance.

- Stainless Steel: Contains at least 10.5% chromium, forming a passive film that provides outstanding corrosion resistance.

Steel Performance Characteristics

The performance of steel is determined by its chemical composition, purity, microstructure, solidification behavior, and subsequent heat treatment. Key engineering properties include:

- Strength and toughness: Adjustable across a wide range through carbon content, alloying, and heat treatment, supporting both general-purpose and high-strength structural grades.

- Wear resistance and hardness: Strongly related to carbon content, hardenability, and microstructural phases such as pearlite or martensite.

- Weldability and machinability: Influenced by sulfur and phosphorus levels, inclusion morphology, and grain size, which affect process stability and ease of fabrication.

- Corrosion resistance: Alloying elements such as chromium, nickel, and molybdenum significantly enhance resistance to humidity, marine conditions, and chemical exposure.

Together, these properties allow steel to serve in applications that demand strength, durability, and predictable performance under varying loads and environments.

Applications of Steel

Because of its strength, ductility, manufacturability, and cost efficiency, steel is used across nearly every major industrial sector, including:

- Structural engineering: Beams, columns, bridge sections, and pressure-retaining structures.

- Mechanical components: Shafts, gears, flanges, connectors, and precision-machined parts.

- Transportation: Automotive chassis, shipbuilding structures, railway systems, and heavy transport equipment.

- Energy and heavy industry: Wind turbine frames, power-generation components, high-temperature assemblies, and oil & gas equipment.

- Steel castings: Pump housings, valve bodies, wear-resistant components, brackets, and casings requiring high strength and impact resistance.

In practical engineering, steel selection is determined by required performance, manufacturing routes, cost targets, and the operating environment of the final component.

Common Questions About Steel

Is steel magnetic?

Most carbon steels and low-alloy steels are magnetic because their microstructure contains ferrite.

Austenitic stainless steels (such as 304 and 316) are generally non-magnetic or weakly magnetic, depending on the amount of cold work and phase transformation.

Does steel rust?

Yes. Without sufficient chromium (≥10.5%) to form a stable passive film, steel will corrode in the presence of moisture and oxygen.

Stainless steels resist rust through their chromium-oxide passive layer, but they may still corrode in chloride-rich or high-temperature environments.

Is steel 100% pure iron?

No. Pure iron is rarely used in engineering applications.

Steel is a complex alloy system composed of iron + carbon (0.02–2.1%) + other alloying elements, and its performance depends on composition design, purity control, and metallurgical processing—not on iron content alone.

Conclusion

Steelmaking is a highly controlled metallurgical process, and each stage directly influences the quality, purity, and performance of the final material.

Primary steelmaking establishes the fundamental chemical composition, secondary steelmaking refines the molten steel through deoxidation, desulfurization, degassing, and inclusion control, and casting determines the solidification structure that governs density, segregation, and internal soundness.

For engineers and manufacturers, understanding how steel is made provides a stronger basis for material selection, casting feasibility, heat-treatment planning, and long-term performance evaluation. When assessing steel casting projects, selecting the appropriate grade, confirming viable casting routes, and anticipating machining or service-environment requirements all depend on a clear understanding of these metallurgical principles.

If you are considering a steel casting application, feel free to upload your drawings or contact our engineering team. We can support you with material recommendations, process selection, and a detailed DFM assessment tailored to your project.