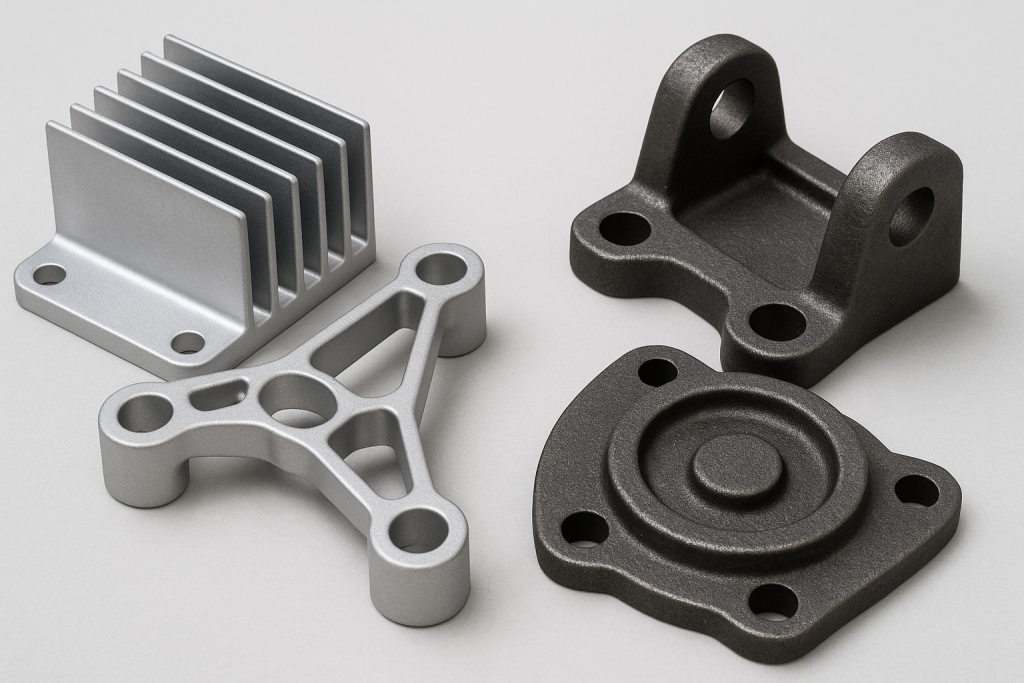

Cast aluminum and cast iron represent two of the most widely used metal families in modern manufacturing. They are often compared not because one can replace the other, but because both materials address similar functional needs with entirely different engineering strategies. Designers frequently face a decision: should a component be lightweight and corrosion resistant, or should it be dimensionally rigid, vibration stable, and economical in mass production?

Choosing between cast aluminum and cast iron rarely comes down to a single property. Strength values alone do not determine durability, and density alone does not define performance. A suitable material must support the way a component performs within a complete system—how it carries load, how it resists deformation, how it handles vibration, and how it withstands environment and time.

To understand this decision, it helps to first examine what each material is and how it behaves when put to work.

What Is Cast Aluminum?

Cast aluminum refers to Al–Si based alloys shaped through molding processes such as sand casting, gravity casting, and die casting. Although pure aluminum is relatively soft, alloying and heat treatment greatly improve mechanical strength. Its natural oxide film provides inherent corrosion resistance, especially in moist or salt-rich environments. Most cast aluminum alloys also exhibit excellent fluidity, making them suitable for thin walls, intricate shapes, and lightweight structural housings.

Cast aluminum heat sink bracket with fins and mounting features

The key value of cast aluminum is not simply low density, but the freedom it gives engineers to combine complex geometry, functional surfaces, and weight reduction in a single piece. Instead of adding bulk for strength, designers can redistribute material, creating ribs, pockets, and integrated structures that take advantage of aluminum’s shape efficiency.

What Is Cast Iron?

Cast iron is a family of Fe–C–Si alloys characterized by graphite structures—flake-shaped in gray iron or spherical in ductile (nodular) iron. This internal graphite phase enables high stiffness, vibration damping, and wear resistance. Gray iron offers excellent dimensional stability and damping for industrial equipment, while ductile iron provides significantly higher strength and toughness for heavy-load and safety-critical components.

Cast iron pipe fitting elbow component for fluid flow systems

The value of cast iron lies not simply in mechanical strength but in the way it maintains shape and tolerances under load. Even at moderate tensile strength, cast iron resists bending, suppresses vibration, and provides stable fits between mating parts. These behaviors result from its intrinsic constitution rather than geometry, which is why cast iron remains indispensable in machine bases, braking systems, pumps, and heavy structural housings.

Cast Aluminum vs Cast Iron: Key Differences

Strength and Stiffness

Heat-treated cast aluminum can reach tensile strengths comparable to certain grades of ductile iron. However, stiffness—not strength—is often the limiting factor. Cast aluminum bends more under load; a component may not fracture, yet dimensional change can still cause functional failure. Misalignment, vibration, or noise may occur long before breakage.

Cast iron maintains shape under load due to its high modulus of elasticity. It preserves straightness, flatness, and precision fits even with moderate tensile strength. This makes stiffness—not tensile strength—the determining factor in components such as machine beds, brake parts, compressor housings, and precision structural supports.

Weight and Structural Efficiency

Cast aluminum is one-third the density of cast iron, but lightweight design is not guaranteed by material substitution alone. To control bending or vibration, cast aluminum often requires thicker sections or ribs, reducing or eliminating mass advantage. In some cases, a cast aluminum structure can become heavier than an equivalent cast iron part.

Cast iron, although heavier, may achieve required stiffness with thinner sections because rigidity is inherent. In machinery and heavy equipment, weight contributes to stability. Mass becomes a functional asset, not a penalty.

Vibration and Stability

Cast aluminum transmits vibration easily due to its low damping capacity. In high-speed or repetitive load environments, this can introduce resonance, noise, and accelerated wear unless external damping or additional stiffness is integrated.

Cast iron provides exceptional vibration damping. Graphite particles convert vibrational energy into heat, preventing resonance. This improves precision, reduces wear, lowers noise, and extends tooling life. For this reason, cast iron remains the foundational material for machine tool bases, brake rotors, die casting molds, and heavy-duty industrial housings.

Corrosion and Maintenance Across Lifecycle

Cast aluminum naturally forms a protective oxide layer and performs well in humid, outdoor, or marine environments. It may still receive coatings or anodizing in extreme conditions but generally demands low maintenance.

Cast iron requires protective coatings when used in corrosive or outdoor environments. Maintenance cost—not rust alone—defines suitability. In controlled indoor settings, cast iron remains durable and economical; outdoors, long-term protection must be considered in lifecycle budgeting.

Manufacturing and Repair

Cast aluminum machines quickly, produces minimal tool wear, and can often be weld-repaired, especially for prototypes, evolving designs, or service-related modifications.

Cast iron machines cleanly and holds tolerances well, but welding and structural repair are difficult. Once a design is mature and stable, cast iron becomes highly cost-efficient in volume production. For frequently revised products, cast aluminum generally carries lower design risk due to easier modification.

Advantages of Cast Aluminum

-

Reduces system weight, improving efficiency in vehicles, robotics, drones, and portable equipment.

-

High thermal conductivity enables housings to function as heat exchangers in motors, batteries, and electronics.

-

Supports thin walls, internal channels, and integrated functional geometry.

-

Can be modified or weld-repaired to support iterative engineering or field service needs.

Advantages of Cast Iron

-

Maintains dimensional stability and precise fits under load due to high stiffness.

-

Superior damping protects precision, reduces noise, and minimizes wear and tool damage.

-

Excellent wear resistance extends service life in friction-heavy applications.

-

Economical for large, heavy, or stable product designs where weight is not a penalty.

Applications of Cast Aluminum

-

Automotive lightweight parts such as suspension arms, steering housings, and transmission cases.

-

Electric motor and power electronics housings where cooling and structural support are required.

-

Aerospace and drone components where maneuverability and mass reduction are critical.

-

Marine and outdoor equipment where corrosion resistance reduces maintenance cost.

Applications of Cast Iron

-

Machine tool beds, columns, and fixtures requiring vibration stability and dimensional precision.

-

Brake rotors and drums requiring thermal stability and wear resistance under friction loading.

-

Pumps, compressors, and valve bodies requiring stable sealing and precise geometry under pressure.

-

Industrial bases, heavy housings, and supports where mass enhances operational stability.

How to Choose Between Cast Aluminum and Cast Iron

-

Choose cast aluminum when reducing mass directly enhances efficiency, responsiveness, or mobility.

-

Choose cast iron when deformation, vibration, and dimensional stability directly influence performance or precision.

-

Cast aluminum is preferable when designs are evolving or require frequent repair.

-

Cast iron is preferable for stable, high-volume products used in controlled environments.

-

Consider lifecycle cost: cast aluminum reduces maintenance, while cast iron reduces cost at scale.

Conclusion

Cast aluminum and cast iron are not opposing materials but tools for solving different engineering problems. Cast aluminum enables lightweight, thermally efficient, and design-integrated parts with adaptive flexibility. Cast iron guarantees stiffness, wear resistance, and long-term precision where geometry must remain unchanged.

The best material is the one that sustains system performance over its lifecycle. When design requirements are understood in context, cast aluminum and cast iron each succeed by serving specific engineering objectives.

If you have application details or drawings, we can evaluate your requirements and recommend the most suitable casting material and manufacturing process.