In the world of metallic materials, steel selection directly impacts structural safety and production costs. From basic iron-carbon compositions to complex multi-element alloy ratios, different types of steel exhibit clear dividing lines in physical performance and chemical stability. Understanding these differences helps achieve a scientific balance between performance and budget in engineering design.

The following content systematically outlines the two most core material categories in industrial applications—Alloy Steel and Carbon Steel—across definitions, classifications, performance boundaries, and application dimensions.

What is Alloy Steel?

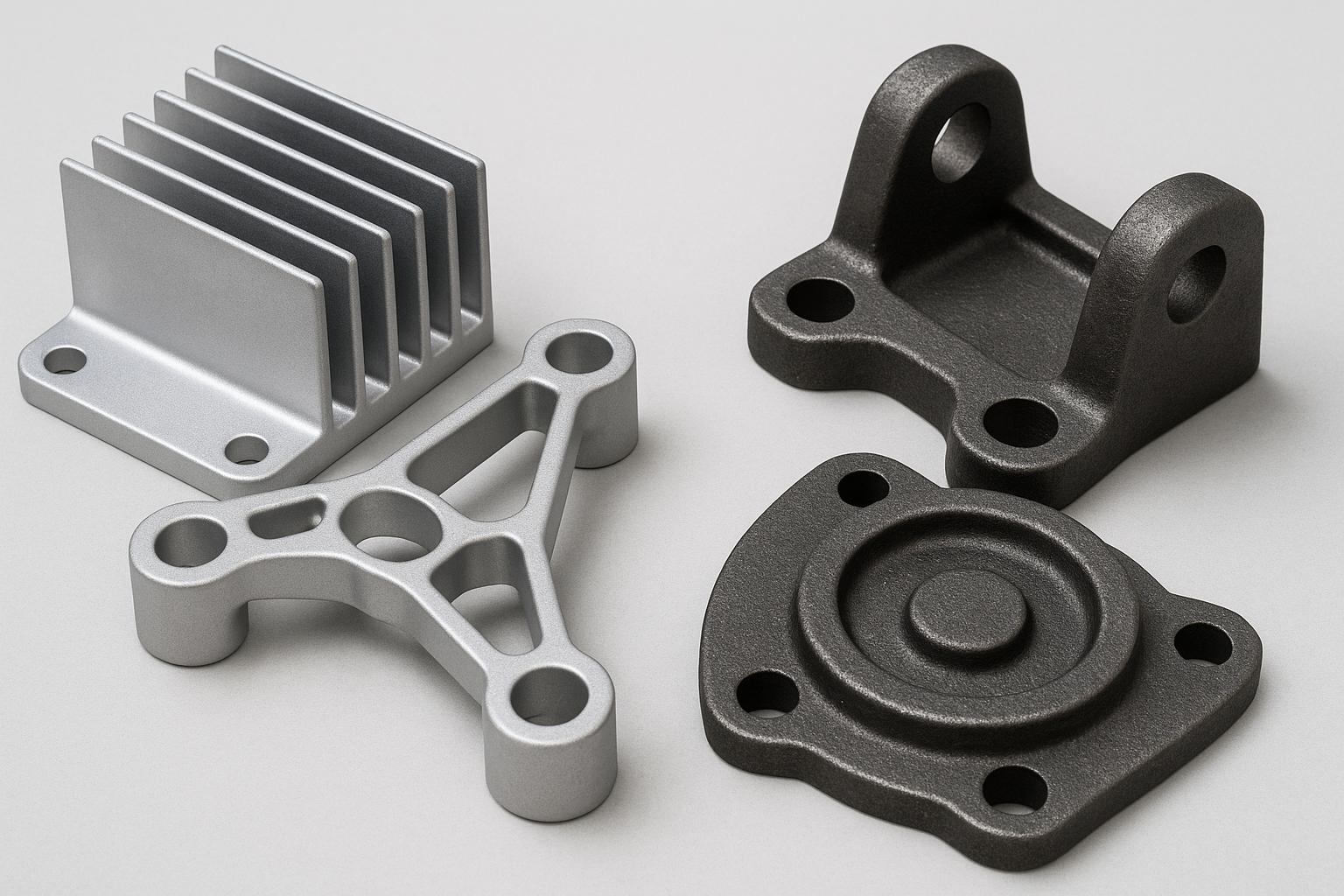

Alloy steel is made by adding elements such as chromium, nickel, molybdenum, vanadium, and manganese to carbon steel. The introduction of these alloying elements is intended to change the microstructure of the metal,

providing targeted improvements in hardness, toughness, corrosion resistance, or temperature stability to meet demanding conditions that basic carbon steel cannot handle.

Types of Alloy Steel

The classification of alloy steel usually focuses on the purpose of the modification and the total element content:

- Low-Alloy Steel: Total alloy content is usually below 5%. The focus is on improving yield strength, fatigue life, and low-temperature impact toughness while keeping costs controllable.

- High-Alloy Steel: Alloy content is greater than 5%. A typical example is stainless steel, which provides extreme chemical and thermal stability through high proportions of alloying elements.

Pros and Cons of Alloy Steel

Alloy steel solves extreme failure problems in complex engineering but changes the supply chain investment structure:

- Pros: High operational reliability; it maintains structural integrity under extreme pressure, alternating stress, or high/low-temperature environments. It also offers low maintenance redundancy due to its internal resistance, significantly extending the service life of components.

- Cons: High initial procurement price, often influenced by the fluctuating prices of precious metals and complex smelting processes. Furthermore, it requires strict process control, such as specific welding heat input and precise heat treatment curves.

Applications of Alloy Steel

Alloy steel serves as a critical node material for sectors with high safety and performance redundancy requirements:

- Core Transmission Systems: Applied in aero-engine components, high-performance gears, heavy-duty crankshafts, and precision bearings.

- Extreme Condition Equipment: Used for deep-sea oil and gas drilling tools, chemical high-pressure reactors, supercritical boilers, and pressure vessels.

- Precision Tooling: Includes high-hardness cold/hot work die steels, high-speed drill bits, and precision medical surgical instruments.

What is Carbon Steel?

Carbon steel refers to an iron-carbon alloy where carbon is the primary alloying element, with a carbon content typically ranging from 0.02% to 2.11%. During the smelting process, no significant amounts of other alloying elements are intentionally added, except for small quantities of manganese and silicon.

The mechanical properties of carbon steel depend heavily on the distribution of carbon atoms within its structure. As the most fundamental industrial raw material, it forms the cornerstone of modern industry due to its mature smelting process and high production consistency.

Types of Carbon Steel

The performance of carbon steel changes significantly as carbon content increases. Based on the carbon content gradient, it is generally classified into three categories:

- Low Carbon Steel (Mild Steel): Carbon content is usually below 0.25%. It possesses excellent plasticity and weldability, making it the preferred material for construction components and sheet metal.

- Medium Carbon Steel: Carbon content ranges from 0.25% to 0.60%. Through heat treatment, it achieves a good balance of strength and toughness, commonly used for manufacturing shafts and load-bearing parts.

- High Carbon Steel: Carbon content exceeds 0.60%. After quenching, it exhibits extremely high hardness and wear resistance, primarily used for professional cutting tools, springs, and high-strength steel wires.

Pros and Cons of Carbon Steel

During the selection phase, enterprises must objectively weigh the inherent attributes of carbon steel against the service environment to mitigate failure risks:

- Pros: High economic cost-efficiency due to abundant raw materials and low smelting energy consumption, suitable for mass standardization. It also offers excellent manufacturability, with low tool wear during cutting, forming, and conventional welding processes.

- Cons: High sensitivity to environmental oxidation; it lacks corrosion-resistant alloying elements and is prone to electrochemical corrosion in humid environments. Additionally, its limited hardenability makes it difficult for large-section parts to achieve core-level strengthening.

Applications of Carbon Steel

Due to its high cost-performance ratio, carbon steel builds the basic infrastructure of modern industry:

- Construction Infrastructure: Widely used in rebar, I-beams, bridge support frames, and municipal water pipelines.

- General Components: Found in automotive body panels, standard fasteners (bolts/nuts), and metal casings for household appliances.

- Basic Machinery: Used for wear-resistant liner plates in non-corrosive environments, agricultural machinery structures, and various general hand tools.

Alloy Steel vs. Carbon Steel: Comparison Table

The following table benchmarks the six core dimensions most critical to material selection:

| Evaluation Dimension | Carbon Steel | Alloy Steel |

| Corrosion Resistance | Lower (Relies on external protection) | Higher (Self-passivation layer) |

| Mechanical Strength | Moderate (Limited strength-toughness balance) | Extremely High (Multi-element reinforcement) |

| Machinability | Excellent (Easy to cut and weld) | Average (Prone to work hardening) |

| Cost | Initial procurement price advantage | Life cycle cost (TCO) advantage |

| Wear Resistance | Depends on carbon content (Risk of brittleness) | Extremely High (Alloy carbide strengthening) |

| Heat Resistance | Prone to softening at high temperatures | Excellent (High creep and thermal strength) |

Alloy Steel vs. Carbon Steel: What is the Difference?

To more intuitively demonstrate the selection logic, we can analyze the specific industrial performance differences across several key dimensions.

Corrosion Resistance

Alloy steel (especially grades containing chromium and nickel) can form a dense protective oxide film through surface self-passivation, significantly reducing the chemical erosion rate of the metal substrate by environmental media. In contrast, carbon steel lacks corrosion-resistant alloying elements and is highly prone to oxidation, forming rust layers in exposed environments.

Mechanical Strength

Alloy steel utilizes multi-element strengthening mechanisms to significantly increase yield strength while maintaining excellent impact toughness. This provides a higher safety margin under sudden shock loads or alternating stresses. The strength of carbon steel is primarily driven by carbon content; however, increasing strength often comes with a decrease in toughness (leading to brittle fracture).

Machinability

Alloy steel, due to its higher hardness and enhanced toughness, causes greater wear on cutting tools and often undergoes work hardening during processing. Furthermore, it requires strict temperature control during welding, which increases manufacturing time and labor costs. Conversely, carbon steel exhibits excellent machinability and welding adaptability with low cutting resistance and a lower technical threshold.

Cost

In a Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) evaluation, alloy steel often demonstrates superior economic benefits for critical heavy-duty parts by reducing maintenance frequency and unplanned downtime. Carbon steel, however, offers a definitive advantage in initial procurement prices, though its maintenance costs may be higher in corrosive environments.

Wear Resistance

Alloy steel incorporates elements like chromium, molybdenum, and vanadium to form extremely hard carbides. This provides exceptional surface wear resistance while maintaining core toughness, extending the service life of components in high-friction environments. The wear resistance of carbon steel relies mainly on increasing carbon content, but high carbon levels can make the material brittle.

Heat Resistance

Alloy steel, through the addition of molybdenum and vanadium, enhances its thermal strength, allowing it to maintain stable mechanical properties and oxidation resistance under high-temperature and high-pressure conditions. At high temperatures, the atomic activity in carbon steel increases, leading to creep and softening, which results in a loss of load-bearing capacity.

Alternative Materials to Consider

In some engineering scenarios, the choice extends beyond the traditional alloy vs. carbon steel debate. Specialized requirements for weight, extreme hygiene, or unique manufacturing processes may necessitate the following alternatives:

Stainless Steel

Often viewed as the premium evolution of alloy steel, stainless steel contains a minimum of 10.5% chromium. This high concentration creates a nearly impenetrable barrier against oxidation. It is the definitive choice for industries where hygiene and aesthetics are non-negotiable, such as pharmaceutical manufacturing, commercial kitchens, and medical instrumentation.

Tool Steel

When your project involves shaping, cutting, or molding other metals, tool steel is the specialized alternative. These are ultra-high-performance alloys designed to maintain a razor-sharp edge and structural stiffness even when subjected to intense friction and red-hot temperatures. They are the backbone of industrial dies, punches, and high-speed drills.

Cast Iron

For massive, stationary structures that require high vibration damping rather than flexibility, cast iron remains a viable alternative to carbon steel. Its high carbon content (above 2%) makes it brittle but exceptionally easy to cast into complex geometries. It is commonly found in engine blocks, heavy machine tool bases, and municipal manhole covers.

Aluminum Alloys

When “strength-to-weight ratio” is the primary engineering metric, aluminum becomes a strong competitor. While it lacks the sheer load-bearing capacity of alloy steel, its significant weight savings and natural resistance to environmental decay make it a top-tier choice for the aerospace industry and modern electric vehicle chassis.

Conclusion

Material selection is a dynamic balance between engineering safety margins and financial budgets. For standardized, low-risk structures, it is recommended to leverage the cost competitiveness of carbon steel. For critical nodes, harsh service environments, or long-cycle operational requirements, alloy steel is the technical guarantee for continuous and stable system operation.

Unsure which material is right for your application? Contact us today, and we will provide a free, detailed material cost-benefit analysis based on your load requirements, budget, and service environment.